Long before May 1st became a symbol of the workers’ struggle, strikes, and the demand for an eight-hour workday, this date was celebrated as a festival with much deeper roots—roots found in myth, fire, and agrarian rituals across Europe, particularly within Slavic mythology and pagan spring rites.

In ancient Slavic societies, the transition from April to May marked the time when the young Svarozhich, the divine son of the god Svarog, would rise from the underworld. This moment signified the beginning of a new vegetative year, a symbolic return of light, warmth, and life. On the night between April 30th and May 1st, people celebrated the Night of Fire—a time when bonfires were lit in the fields and meadows, not merely to illuminate the night, but to invoke fertility, protection, and purification.

At the heart of every Slavic ritual fire often stood a pillar—a sacred post symbolizing the axis mundi, the world’s axis, but also the phallic principle, fertility, and the connection between the heavens, the earth, and the underworld. Around it, people danced and sang, calling upon the forces of nature, dedicating the entire ritual to the awakening of life.

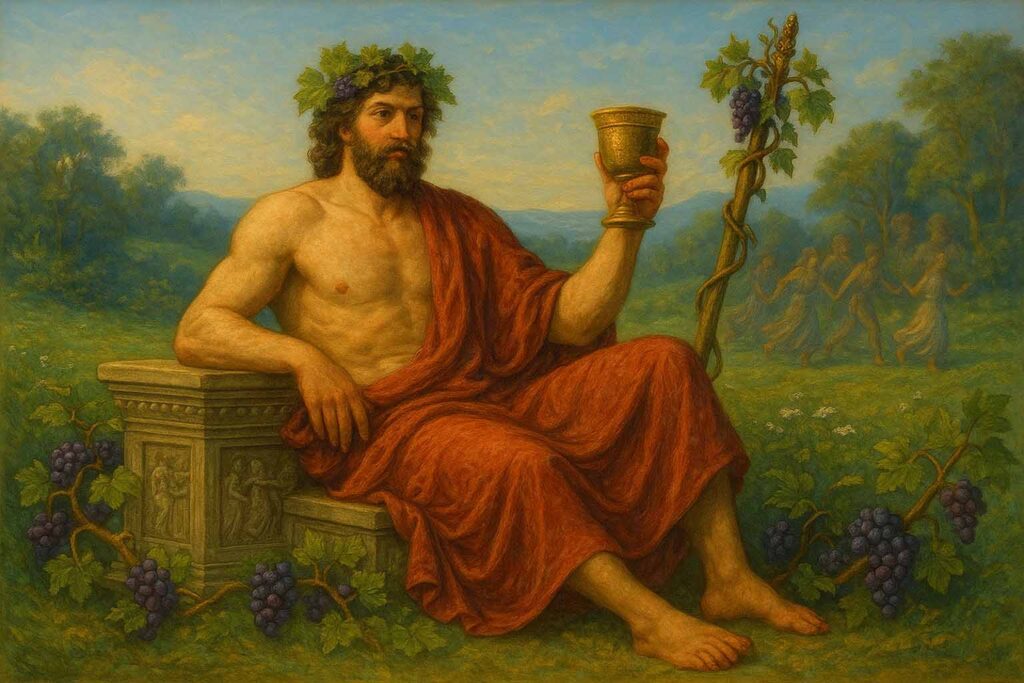

Similar customs can be found among the Celts in their celebration of Beltane, the Germans in Walpurgis Night, and in ancient Greece—where May 1st was linked to spring festivities in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine, ecstasy, and vegetation. Among the Slavs, young couples would leap over the fire, symbolically burning away the old and stepping into a new cycle—just as Svarozhich emerged from the earth to bestow fertility upon the world.

Later, through Christian history and various political eras, the meaning of this day shifted, but the flame endured—both literally and symbolically. Today’s protests, gatherings, and workers’ assemblies are, in truth, a modern variation of the same ancient principle: emergence from darkness, a struggle for light and warmth—just in a different form.

Mythological Roots of May Day in Slavic Tradition

Long before May Day became associated with political struggle or labor movements, it marked a sacred point in the seasonal calendar of ancient Slavic peoples. For them, this time of year carried profound spiritual and mythological significance, rooted in the eternal dance between light and darkness, death and rebirth, dormancy and fertility.

At the heart of this tradition was Svarozhich, the young god of fire and the son of Svarog, the celestial blacksmith and sky-father of Slavic mythology. As the earth warmed and winter’s grip loosened, Svarozhich was believed to emerge from the underworld—a symbolic rebirth that paralleled the awakening of the land itself. His ascent was not just a seasonal marker but a cosmic event, announcing the return of vitality, warmth, and growth to a world that had slumbered in the cold.

This transition was celebrated on the night between April 30th and May 1st, when bonfires lit the fields and hilltops in what was known as the Night of Fire. These fires were not mere celebrations—they were rituals of transformation, intended to summon fertility, protection, and the cleansing of stagnant energies. They served as both beacons and portals: drawing divine attention from above, while also warding off malevolent forces lurking in the liminal space between seasons.

Central to many of these ceremonies stood a ritual pillar—a wooden post, often carved and decorated, representing the axis mundi, or world axis. This pillar united the three cosmic realms: the heavens above, the earthly plane, and the underworld below. But it also held deep associations with fertility, standing as a phallic symbol that invoked the union of masculine and feminine forces to ensure the flourishing of crops, animals, and communities.

Around this sacred axis, people would dance, sing, and perform rites to awaken the life-force slumbering in nature. These were not merely symbolic actions; they were believed to stir the very energies of the earth, encouraging growth, abundance, and harmony.

In Slavic cosmology, time was cyclical, not linear. The emergence of Svarozhich each spring was not a one-time event, but part of a perpetual cosmic rhythm—a drama re-enacted every year through ritual and myth. And so, May Day was not merely a marker of agricultural change but a portal into deeper spiritual dimensions: a celebration of light triumphing over darkness, of renewal rising from decay, and of sacred fire re-igniting the web of life.

Ritual Fires and the Sacred Pillar in Slavic Traditions

The bonfires of the Slavs, lit during the transition from April to May, were not simply festive gatherings—they were deeply encoded ceremonial acts that carried layers of cosmological meaning. Known across various regions as the Night of Fire, this liminal moment marked a sacred threshold between the dying of the old and the awakening of the new.

The lighting of fires in fields, meadows, and hilltops served multiple purposes. Practically, it was a signal to the community and a symbolic cleansing of the land. Spiritually, fire functioned as a purifier, protector, and inviter—cleansing the space of dark forces, safeguarding the crops from unseen dangers, and inviting divine presence into the earthly realm. These flames echoed the primordial fire of Svarozhich himself, whose ascent from the underworld was mirrored in the fire’s leap toward the sky.

At the center of these rituals often stood a wooden pillar—a sacred post planted firmly in the earth. This was no random object. It represented the axis mundi, the world axis that connected the heavens, the mortal world, and the chthonic underworld. It was both cosmic and carnal, symbolic of divine order and also of the creative, fertile force embodied in nature and human life.

This pillar often took the form of a carved or adorned tree trunk or totem, erected in the middle of the gathering. Around it, communities would dance in circles—ritual movement meant to stir the energies of nature and align human rhythm with cosmic cycles. The dances were accompanied by songs, invocations, and offerings to the spirits of the land, ancestors, and deities.

In its shape and position, the pillar was phallic, evoking the male principle of fertility and the power of penetration—both in terms of planting seeds in the earth and in the metaphysical sense of linking dimensions. It was often associated with sunlight, fire, and masculine vitality, while the earth around it, fertile and receptive, represented the feminine womb of nature.

Preserved in folk memory and ritual dance, this axis was more than a relic—it was a living symbol of balance, renewal, and sacred connection. Though later absorbed and obscured by Christian reinterpretations or political redirections, the image of people gathering around a central post and leaping through fire still echoes across Slavic lands each spring.

Parallels with Other European Pagan Traditions

The celebration of May 1st is deeply rooted in ancient pagan customs, and this connection is not limited to a single culture or region. Across Europe, various pagan traditions share striking similarities in their symbolic elements, goals, and rituals. Below are a few prominent examples of springtime celebrations that parallel the May Day festivities.

Beltane among the Celts

Beltane, celebrated on April 30th and May 1st, was one of the major fire festivals for the ancient Celts. Like the May Day festivities, it marked the arrival of summer and the fertile season. Bonfires were lit to honor the sun, and people would leap over the flames to ensure prosperity, health, and fertility. The Maypole, a central symbol of modern May Day celebrations, also finds its roots in Beltane, symbolizing the connection between life and the cyclical nature of the seasons. The themes of renewal, fertility, and the sacred marriage between the Earth and the divine are central to both Beltane and May 1st rituals.

Walpurgis Night among the Germans

Walpurgis Night, celebrated on April 30th to May 1st, is a Germanic tradition that marks the end of winter and the welcoming of spring. It is often associated with witches, fire, and the banishment of dark forces. In many ways, Walpurgis Night shares the same celebratory spirit as May Day, with its emphasis on fire as a purifying element and the themes of fertility and protection against evil. The lighting of fires on hilltops and the use of masks to ward off malevolent spirits create a strong connection between the rituals of Walpurgis and those of Beltane and May Day.

Dionysian Festivals in Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece, the Dionysian festivals, particularly those celebrated in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and revelry, also took place during spring, around the same time as May Day. These festivals were marked by wild feasts, dancing, and performances, all of which were meant to honor the divine forces of nature and the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The themes of liberation, fertility, and the celebration of life are similar to those found in May 1st rituals. The connection between the cycles of nature, fertility, and community bonding unites the Dionysian celebrations with the spirit of Beltane and Walpurgis Night.

Similarities in Symbolism, Elements, and Goals

While these traditions differ in specific practices, there are remarkable similarities in the symbolism and elements they emphasize. Common themes include:

- Fire as a purifying and life-giving force: Bonfires are central to all of these traditions, representing the sun, light, and the triumph of life over darkness.

- Fertility and renewal: The rituals often center around fertility, both of the land and of the people, symbolizing growth, abundance, and new beginnings.

- The connection between the spiritual and natural worlds: These celebrations honor deities or natural forces associated with fertility, harvest, and seasonal change, underscoring humanity’s deep connection to the cycles of the Earth.

In all of these traditions, the arrival of spring is seen not only as a seasonal shift but as a time to rekindle vitality, celebrate abundance, and reaffirm human relationships with the divine and the natural world.

Transformation of Meaning Through Christianity

As Christianity spread across Europe, many pagan rituals and celebrations were either suppressed or transformed to fit within the new religious framework. The celebration of May 1st, with its deep roots in pagan traditions, was no exception. Over time, the meaning of these springtime rituals evolved as they were adapted by the Church, often as a way to suppress pagan beliefs while incorporating elements that were familiar to the people.

How Pagan Rituals Were Suppressed or Cloaked

When Christianity began to dominate Europe, one of the strategies used to bring pagans into the fold was to adapt or Christianize their celebrations. Rather than outright prohibiting these festivals, the Church often redefined the meaning behind the rituals to align them with Christian values and beliefs. This process often involved replacing pagan deities with Christian saints or symbols, as well as reinterpreting the underlying themes of fertility, nature, and renewal in a Christian context.

For example, the ancient pagan practice of celebrating the fertility of the Earth through rituals and sacred marriages was shifted to honor Christian figures, such as the Virgin Mary, whose feast day is celebrated in May. The Maypole, a symbol of fertility and life, became associated with celebrations of the Virgin Mary in some Christian communities, subtly replacing the pagan elements with Christian imagery. The focus on nature and fertility became more about honoring God’s creation rather than celebrating the natural cycles through pagan gods and goddesses.

Christian Holidays Near May 1st and Their Adaptation

Several Christian holidays have roots in, or coincide with, pagan traditions around May 1st. The most prominent among these is Feast of St. Joseph the Worker, celebrated on May 1st in the Catholic Church. This feast day was established in 1955 by Pope Pius XII to provide a Christian alternative to the secular May Day celebrations, which were increasingly associated with labor movements and socialist ideologies. By placing this feast day on the same date as the traditional pagan celebrations, the Church sought to provide a Christian framework for honoring work, labor, and the dignity of workers, while also maintaining the connection to the season of renewal and growth.

Additionally, the Feast of the Virgin Mary, Queen of May is celebrated during the month of May, often with May Crowning ceremonies. These ceremonies, in which a statue of the Virgin Mary is crowned with flowers, echo the earlier pagan customs of honoring the divine feminine and celebrating the fertility of the Earth. Though the religious focus has shifted to honoring the Virgin Mary, the symbolism of renewal, growth, and the sacred feminine remains present.

The Subtle Reworking of Pagan Celebrations

In many ways, Christianity did not completely erase the ancient pagan traditions but instead recontextualized them. The symbolism of fire, fertility, and renewal continued to thrive in Christianized forms, even though the direct worship of nature gods and goddesses was replaced by veneration of saints and Christian figures. For example, the bonfires associated with Beltane or Walpurgis Night found new life in the form of Easter fires in many Christian traditions. These fires, which were lit on the night before Easter, symbolized the victory of light over darkness, a theme closely aligned with the pagan celebration of the return of the sun.

Modern May Day as International Workers’ Day

In its modern form, May 1st has become International Workers’ Day (or Labour Day), a global celebration of labor rights and the working class. However, the transformation of this date from a pagan celebration of fertility and renewal into a day dedicated to workers’ struggles and rights involves a fascinating historical journey. The connection to the ancient themes of renewal, struggle, and light overcoming darkness remains, even as the meaning has shifted.

The Origins of the Modern Holiday (Haymarket, USA)

The roots of International Workers’ Day trace back to the labor movement in the United States, specifically to the Haymarket affair in Chicago, 1886. The event was a peaceful rally for workers advocating for an eight-hour workday that tragically turned violent when a bomb was thrown at the police, leading to the deaths of several police officers and civilians. In the aftermath, several labor activists were arrested, and the event became a symbol of the struggle for workers’ rights.

The origins of May 1st as a day of labor and solidarity are directly linked to this pivotal moment in American history. In 1889, the Second International, a gathering of socialist and labor parties, declared May 1st to be International Workers’ Day in honor of the Haymarket martyrs and to promote the cause of labor rights worldwide.

Connection to Ancient Symbols: Fire, Struggle, Emergence from Darkness

Even though the modern celebration of May 1st is focused on labor rights, its symbolism still contains echoes of the ancient rituals. The struggle for justice, the fight against oppression, and the emergence from darkness are all central themes in both the pagan celebrations and the modern workers’ struggles.

- Fire, once a symbol of the sun’s power and life’s renewal, continues to be an important element in labor protests and May Day rallies. In many cities, people light bonfires or carry torches as a symbol of their fight for workers’ rights and the burning desire for social change.

- The struggle for justice, as symbolized by the workers’ movement, mirrors the ancient pagan fight against the winter darkness and the triumph of light over shadow. In both contexts, there is a sense of pushing through adversity toward a better future—whether that means the arrival of summer or the betterment of working conditions.

- Emerging from darkness also reflects the human condition, as the working class strives to break free from the oppression of long hours, low wages, and unsafe working conditions. Just as ancient cultures celebrated the emergence of light and fertility, workers today celebrate their victories over exploitation and inequality.

How the Archetypal Structure Remains the Same Despite Changes in Meaning

Though the specific meanings of May 1st have changed, the archetypal structure underlying the celebration has largely remained intact. The pagan celebrations were centered around themes of renewal, light, and the triumph of life over darkness, and the modern labor movement uses these same symbolic frameworks to express the struggle for dignity, justice, and the rights of workers.

- Renewal: In both the ancient and modern contexts, May 1st represents a fresh start or rebirth. For pagans, it was about the rejuvenation of nature; for workers, it is about the rebirth of justice and workers’ rights.

- Light overcoming darkness: Both pagan and labor rituals focus on the triumph of light (the coming of spring or the victory of justice) over the darkness (winter or exploitation). Even though the nature of the “darkness” has changed, the symbolic fight remains the same.

- Community and solidarity: While ancient rituals were about community connection and shared celebration of nature’s cycles, modern May Day celebrations are about solidarity among workers and the collective fight for a better world. The core of both rituals lies in the unity of people coming together for a shared cause, whether that cause is the celebration of life or the struggle for justice.

Conclusion: The Cyclical Nature of Time and Collective Memory

The cyclical nature of time, marked by the changing of seasons, plays a central role in human consciousness. Just as the Earth moves through its cycles of growth, decay, and renewal, so too does human life mirror these patterns. The ancient rituals that celebrated the arrival of spring, with all of its promises of renewal and vitality, are deeply embedded in our collective memory. Despite the changes in religious and cultural contexts over time, the underlying archetypes of these rituals continue to resonate within us.

How Ancient Patterns Persist in Collective Consciousness

The continuity of ancient patterns through generations is not just a historical curiosity; it is a reflection of how deeply these rituals and symbols are embedded in our collective consciousness. Humans have always been creatures of ritual, using symbols and celebrations to mark important moments in the cycle of life. These symbols, whether they are of fire, fertility, or struggle, remain ingrained in our psyche because they are connected to the very rhythms of nature and the human experience.

Even as the meanings of ancient festivals have shifted—such as when pagan customs were adapted by Christianity or when May Day was transformed into a day for labor rights—the core themes endure. The act of coming together to celebrate life, to acknowledge the cycles of nature, and to reaffirm our connection to the earth and each other is universal. It transcends cultures, eras, and ideologies, highlighting how deeply these patterns are woven into the fabric of human identity.

Why Spring Always Reminds Us of Freedom, Life, and Change

Spring has always been a season of renewal and transformation. After the cold and darkness of winter, the arrival of warmer weather, blooming flowers, and longer days symbolizes the triumph of life over death, light over darkness, and hope over despair. These universal themes are not just physical but also deeply psychological and spiritual.

For many, spring is a time of freedom, as the world around us comes to life again. The constraints of winter are lifted, and the earth is reborn. In this way, spring becomes a powerful symbol of personal and collective freedom—the freedom to grow, to change, and to embrace new possibilities.

Spring also represents life itself, with all of its potential. As flowers bloom, animals emerge, and the cycle of nature begins anew, we are reminded of our own capacity for growth, renewal, and reinvention. In both the natural world and human life, change is inevitable, and with each change comes the opportunity for transformation.

Lastly, change is at the heart of spring. It is a season of transition, where everything seems to shift from one state to another—from the dormancy of winter to the vibrancy of life. This constant cycle of change mirrors the human experience, reminding us that, just like the seasons, we too are always in a state of flux, constantly moving from one phase to the next.

Thus, whether we are celebrating ancient pagan rituals or modern labor movements, the fundamental human desire to connect with the cycles of nature and the archetypes they represent remains strong. May 1st, in all of its forms, serves as a reminder that life is cyclical, that change is inevitable, and that freedom, life, and renewal are always within our reach.